Falling Apart At The Seams

“It’s all a bit shit, isn’t it?”

A comment I’ve heard quite a lot, recently. It’s generally applied to the state of services in the UK, whether public or private.

“Nothing seems to work properly anymore, does itI?” often follows.

The general perception is that everything is falling apart. Our benighted public services are cracking under the twin onslaughts of austerity and the dogma of privatisation, the latter exacerbating the privations caused by the former by introducing unnecessary process and cost and contractual straitjackets that prevent change and adaptation.

But the same can be seen in the commercial space. The relentless pressure for greater ‘efficiency’ (in the dogmatic belief that this will drive profits) means more is demanded from less resources, whilst organisational structures and management approaches that are failing to deliver the desired outcome are clung onto in the belief that we just need to do them more and harder and they will work better.

So nothing works properly. When something goes wrong, you are expected to fix it yourself. “Here’s a link to our website, have you read these FAQs, have you been through the diagnostic process, have you tried switching it off and back on again, I’ll just transfer you to the right department …” and then the line drops as you swear at the cat and throw your mug of tea at the wall.

That’s assuming there’s anyone to ring at all. You may, instead, have to go through some lengthy and badly designed process on their website, inputting all sorts of data and information, only for it to freeze as you try to submit it. After several days and umpteen failed attempts, you simply give up and either decide you can live without whatever you were trying to get sorted, or you find another supplier (who will, in turn, let you down at some point in the future).

“Damn Tim Berners-Lee and his infernal internet that allowed these charlatans to turn me into their customer support agent for the service I am paying them to provide!!”, you think. Your mind slips back to the day when you used to go and get things you wanted from shops and pay with real money, rather than get a load of stuff delivered that’s wrong and takes you ages to return and even longer to get the refund, if ever.

So why is this happening?

Why is it all broken?

I Want It All

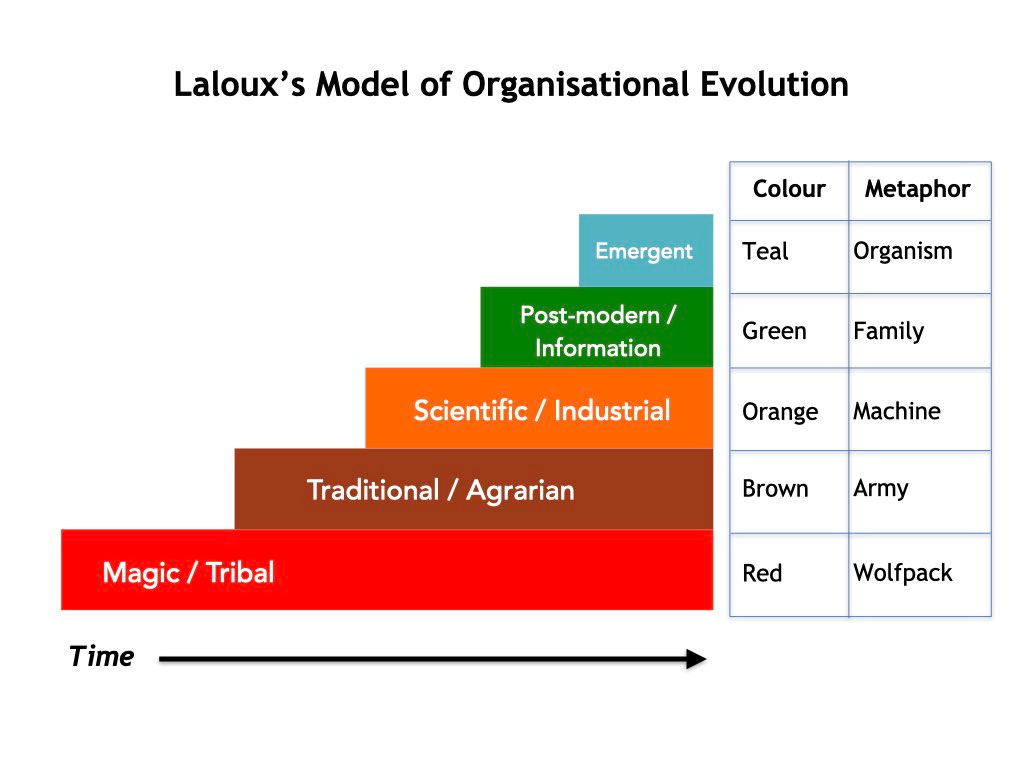

The dominant organisational structure is that of a hierarchy. We are familiar with the pyramid of control and how it distributes power, status, and wealth. It’s been around for centuries and over that time it has changed a bit. In Frederick Laloux’s model (from Reinventing Organizations), he identifies the different types of organisation that have emerged over time and the metaphors we use for each.

Far and away the most dominant today is what Laloux terms Orange but most of us would know by its metaphor, that of a Machine. We speak of ourselves as ‘cogs’ in this machine, we talk about ‘oiling the wheels’, ‘smooth running’ and ‘putting down the accelerator’. Sometimes we use the metaphor of a computer and say things like ‘upgrading the system’ and ‘installing a new OS’, but it’s still a machine, only one that runs with even greater precision and logic.

Therein lies the problem. Our organisational machines are running flat out, they are over capacity and there’s no time for maintenance. They are beginning to degrade in performance and, ultimately, to fail. That’s what we are experiencing today.

You will have seen it in the organisations you are in, or have been in. The processes that don’t work but no-one knows how or has the time to find out how to change them. The projects that everyone knows are going nowhere and delivering nothing useful but are running out of control and seem unstoppable. The dysfunction and dislocation that grows and grows but no-one seems responsible for fixing.

And, as cogs, you will have felt the increasing pressure. You or your coworkers might have lost a few metaphorical teeth under the strain, or even to have broken completely.

I was put on this line of thought by a post by my mate Perry Timms called #affirmation, in which he reiterated his commitment to finding alternatives to this and towards a ‘participatory, liberated, inclusive co-creation of the alternative paradigm of work.’ Or, to paraphrase, self-management.

As Perry puts his case

“In the hierarchical constructs we see waste, ambivalence, detachment and downright subversion of what people should be doing; through social loafing; misdirection, faking, gaming and more.

And we’re still convinced a hierarchy is a more effective and even efficient way of being, to control human beings into a coalesced form of utter conformist application to their tasks and set goals.

And we rarely, if ever, allow ourselves to even contemplate that a loosening of the rigid confines of a hierarchy might just be better.”

Well, it’s time to consider not just loosening but replacing hierarchies. Of course, total eradication is neither possible and or even desirable. We are humans, driven by status, amongst other things, after all. We like a ‘pecking order’ but it needs to serve us, not constrain us.

However, it was Perry’s next observation that really provoked me

“Hierarchies are creating greed. The big issue of our time. Greed is equated to pulverising our planet and burning, extracting and polluting it. To the inequity of wealth and power and the chances to live a prosperous, safe, inclusive and flourishing life. Greed comes from the hierarchy. Greed at the top for power, money and position.”

This is, essentially, driving the breakdown I describe above. Those profits go to the richest, who have grown massively richer during my lifetime. The concentration of wealth is mind-blowing and the growth of inequality is one of the biggest ills of our times and cause of our sickening societies.

Why has this happened? The easy answer is that this is the product, and indeed the intention, of neoliberalism. Look at the people who backed the neoliberal project, they are the same ones who’s wealth has exploded. It has spawned what is called ‘late stage capitalism’, where the pursuit of profit is having all sorts of harmful consequences for people and planet and undermining the capitalist model itself.

But I think there are some other factors that have enabled and accelerated this, that created a favourable wind for the neoliberal project, that deserve a bit more exploration.

Welcome To The Machine

When I entered the workplace in the 1980s, most organisations still ran on paper systems. Personal computers had only just arrived (I used an Apple II and we were early adopters!) and local area networks were unheard of. This meant that recording, assembling and processing data was slow, expensive and difficult, so it was done sparingly. Only the important things got measured.

Processes were also used sparingly because it took a lot of effort to document a process and train everyone in it. This meant there was a lot of slack in the system, a lot of variation and people were required to use their initiative. Whilst this led to inefficiencies in some cases, it also led to innovation and a lot of adaptability.

What we have seen since is a dramatic increase in data, measurement and processes. Organisations have become more efficient, some dramatically so. Let’s be honest, there was a lot of low, hanging fruit to be grabbed and the big consultancies made it their job to grab it - on behalf of their fee-paying clients, of course.

These early successes set in train a series of ‘initiatives’ to make the machine run more efficiently. The more data you had, the more granular you could get with your analysis, the more improvements you could wring out the system. Everything was put into a process so that it could be measured and optimised, even things that didn’t really fit that well into a process. More and more data was collected and processed so managers could control things at an ever more detailed level.

Change programmes were rolled out (and rolled over staff) at increasing frequency because it was now easier and quicker to do so. The gains could be measured and shown as proof to secure the next promotion (and, if they didn’t appear, you just run out another change programme to cover it up).

If you keep doing the same thing then, eventually, the law of diminishing returns will make an appearance. That’s where we are now.

Exerting greater control, cutting resources to improve throughput, streamlining processes, cutting out steps that don’t have an immediate payback, cutting down the ‘maintenance’, sweating assets harder, running down reserves and contingencies, using cheaper materials and all the other little tricks are not working anymore. There are no more gains to be had. In fact, they are starting to have a negative impact.

If you are running an actual machine and you run it as fast as it will go, skip maintenance, rush repairs, use cheap spares and unskilled engineers, it will break. It might slow down to begin with but then there will a catastrophic failure.

I think there are quite a few organisations heading for catastrophic failure.

The easy wins of eighties and nineties, as computerisation and process engineering had an impact, followed by the impact of the internet in the last two decades, have enabled the ‘success’ of neoliberalism. However, it is the very same approaches that yielded those gains that are now causing the breakdown we see around us.

We have been optimised to within an inch of our lives. We are held captive by processes and algorithms (which are arguably a form of process - “The computer says ‘No’”). It’s not working for us, and it’s not working for the organisations either.

We have convinced ourselves that this is the only way to organise ourselves, that a hierarchy is the only approach that makes sense. But that’s not true, and it’s time to try some alternatives.

All power structures are unassailable, until they collapse. We should try and avoid ending up buried in the ruins.

It Doesn’t Have To Be This Way

And on that point, there are many others ways in which we organise ourselves. Indeed, when people push back against self-organisation as being ‘weird’, I point out that it is how we run the rest of our lives and it is organisational life that is ‘weird’.

I came across a timely post by Jeroen Kraaijenbrink, in which he listed the different types of organisation identified by Gary Hamel in his book “The Future of Management”. These are:

Life → Variety

Assumption: Experimentation and learning beat planning

Organizing principle: Evolution through variation, selection, and retention

Distinctiveness: Requires no top-level approval

Markets → Flexibility

Assumption: Market forces beat coordination

Organizing principle: Bring supply and demand together

Distinctiveness: Implies dynamic self-organization

Democracy → Activism

Assumption: Having a voice beats obedience

Organizing principle: Employees decide and vote their leaders

Distinctiveness: Turns power relationships upside down

Religion → Purpose

Assumption: People contribute to what they care about

Organizing principle: Create engagement through purpose

Distinctiveness: Focuses on why, not on what and how

Cities → Serendipity

Assumption: Coincidental meetings drive innovation

Organizing principle: Create ways in which people meet unexpectedly

Distinctiveness: Implies letting go rather than controlling

Our blind adherence to hierarchical command-and-control structures in organisations seems bizarre when you consider the range of alternatives, many of which can be seen in pioneering and progressive organisation (some of which I have highlighted in previous missives).

Consequences

The relentless pursuit of profit has also led to another unintended consequence and feature of late-stage capitalism, that ‘people’ have become another consumable in the business models that organisations are applying.

Exactly how unintended this is is actually open to question. The name change of ‘Personnel’ to ‘Human Resources’ hinted at the inexorable logic of a relentless pursuit of profit above everything else. Indeed, earlier stages of capitalism have had a similar attitude towards ‘labour’, from the slaves that worked the plantations to the factory workers forced to spend their meagre wages in the factory shop and pay rent on their factory houses to factory owner.

However, it is not just physical labour that organisations need today. It’s not even the mindless drudge of sitting at a desk processing admin tasks. They need skills, intellect, creativity - emotional labor, as Seth Godin would call it - that is proving to be harder to find a ready supply of. It turns out that, as the slaves knew, you can command the body but you cannot command the mind. People have agency.

Hence the phenomenon grossly mislabelled as ‘Quiet Quitting’. Hence the flight of professionals from toxic workplaces. Hence the enthusiasm for ‘portfolio careers’ and varied and flexible careers.

Organisations are being hollowed out of the talent and energy that they need because those people have better alternatives and the old inducements of money and status have become much less attractive than autonomy and freedom.

The COVID enquiry taking place in the UK shows us perfectly what the eventual outcome is. The Government was hollowed out of talent because to be a member you had to accept certain ideological positions (essentially being pro-Brexit) and Boris Johnson’s leadership. Many capable, proven ministers were not only put off but actually thrown out of the ruling party, leaving a Cabinet of 2nd-raters (if that) united by groupthink. The Cabinet Office, the part of the civil service that supports the PM and Cabinet, was similarly denuded of talent because people either voted with their feet or were replaced by more pliant (and mostly junior) officials.

Hit by a crisis, in the form of COVID, the organisation lacked the talent, organisation and application to respond effectively. Chaos ensued, with deadly consequences, and we are still suffering in the aftermath. Government is barely functional (see the comment above about public services).

The UK Government will survive (although it will take new management to restore some level of functionality) because governments have to exist and a revolution seems unlikely (we’re British, after all, we don’t like to make a fuss.)

But companies? Well, the consequences for them may be fatal.

insightful